Stories are more fun when we tell them together. Taking that a step further—stories are often more fun when we build them together. There persists this myth of the great artist, working feverishly (and alone) to make a masterpiece, the magnitude of which could only be rendered in an environment of social and creative isolation. And, sure, some great works of art might have been created in those conditions. But there also exists art that seeks to offer responses to the world from a place of interaction and connectivity. Collaborative story building, especially as articulated in games, are creative endeavors of the latter variety.

Sometimes, when people ask me about the form that my own creative endeavors take, I’m unsure how to provide a singular answer. Poems? Yes, I make those. Games? Those too. Sometimes I want to tell them that the biggest thing I do is create spaces that engender opportunities for chance and story building to collide, where it is equally as important to embrace collaboration as it is emotional arc, and where the production of something together of compelling ambiguity and lingering strangeness is the goal, but all of that is a mouthful of pomposity, so I just tell them that I make things.

So, hello. I’m Chris McAllister Williams and I make and teach poems and weird internet artifacts at UWGB. And I’m here to talk to you about the glory of algorithm, chance, and collaborative story building.

To begin extolling the virtue of chance, we need to wade into the waters of emergent narrative. Emergent narrative, as opposed to developer written and created “embedded” narrative, refers to the storyline that is created through player interaction with the systems and algorithms of the game. In other words, emergent narrative happens when the game, through its programming, offers narrative opportunities, but does specify nor control the outcomes of those opportunities. Rather, it is up to the player, through interaction with these narrative spaces, to do that creative work, and to tell that story.

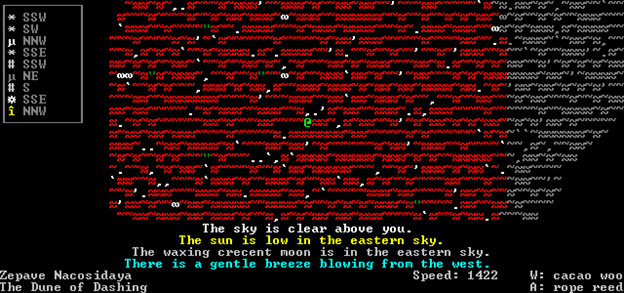

There are many games that embrace this type of game narrative approach. Dwarf Fortress, a difficult to describe roguelike/fortress-construction-simulator where “losing is fun!,” is a key example of this. Minecraft could be considered another. The Sims almost exclusively relies on emergent narrative to engage its players, although it might be possible to read the player as the most important gameplay “system” in the games of that franchise. This approach is acknowledged, has its proponents and detractors, and is present (even if, perhaps, in a small dose) in a large array of contemporary games.

But what I find most exciting is when emergent narrative, which is usually understood to be a story method for single-player game experiences, allows for collaborative story building moments, where it moves beyond game to player and player to player interactions and instead becomes an amalgam of all these things. To my mind, one of the best current expressions of this collaborative exchange is the cultural event of Blaseball.

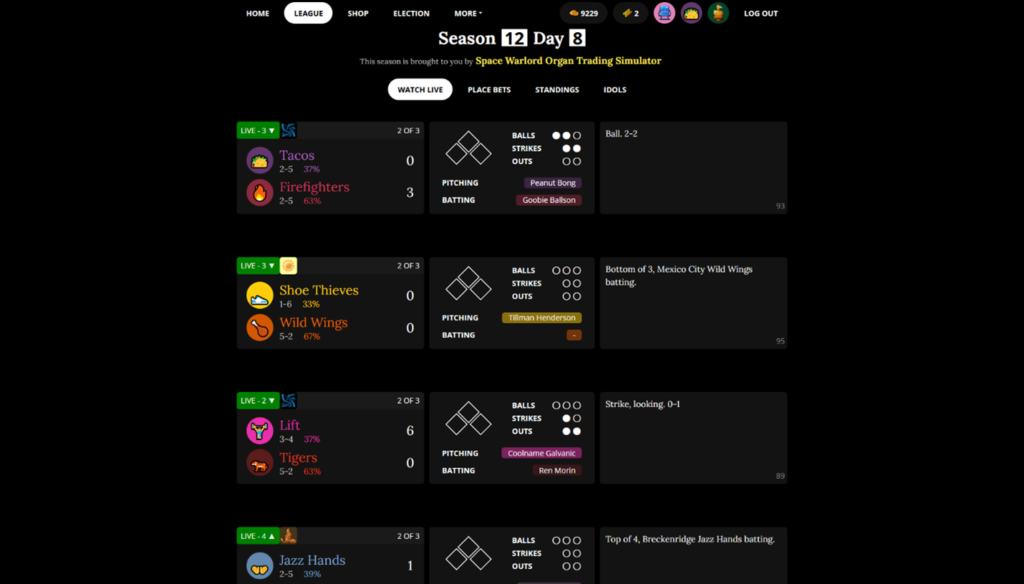

Blaseball began life in 2020 as a project by The Game Band to bring people together over the pandemic and has since evolved into, well, something else. It is, like many games steeped in emergent narrative, not easy to categorize. At its heart, it is a surreal baseball simulator, automating games throughout the course of a single season (a week in real world time) to determine the champions of “The Internet Series of Internet League Blaseball.” Player interaction comes in the form of betting on game outcomes and influencing future algorithmic events through the careful application of votes purchased through betting proceeds. It is a game replete with chance encounters with birds, incineration, and possible encasement in a giant peanut. It is a game that features multiple suns, a forbidden book, and a giant squid entity of undetermined provenance. In short, it is, like Moby-Dick, about everything—joy and sorrow, pain and elation, dangerous pursuit of a single-minded goal, and brave labor in the face of an uncaring and perhaps unknowable god(s). The way I know it is about these things is through the keen interaction of a dedicated and creative fanbase.

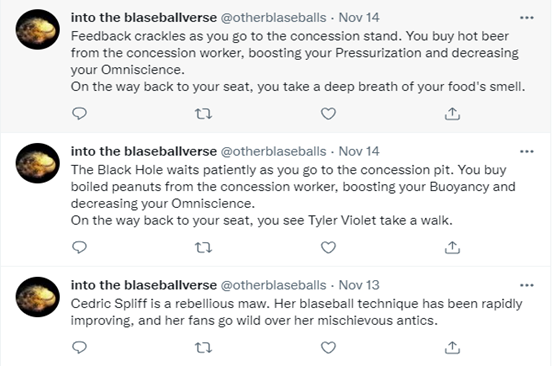

While the game of Blaseball decides the outcome of games (including status effects applied to blaseball players, weather conditions, and the box score) that’s only where the narrative of the true Blaseball experience starts. Fans then interpret that outcome, creating visual art, music, theories, obituaries, and a robust, enthralling history that both extend and complicate the “raw” outcome of the game. If the Blaseball experience ended there, with fan-algorithm interaction, that would position it solidly in emergent narrative territory. But then the collaborative story building element comes into play as other fans interpret the original art created by another fan and produce a new, entirely different, piece of art that develops, refutes, scrutinizes, and explodes that interpretation. Then another fan takes that and makes something new off that art.and so forth. The result is a fractured kind of anti-canon that is utterly fascinating.

The developers of Blaseball are very much aware of the importance of fan interaction–this was understood as the outset of the project as desired result of an inclusive, community-centered experience. This also allows for a kind of recursive design element, where the developers embrace the fan art and theories that emerge out of the game design as part of the design itself. And that’s the true “game” of Blaseball, an interaction that is not binary (game-player, player-player), but resists any stable adjudication of its gameplay.

Blaseball, of course, isn’t the only collaborative game experience that features algorithm and the interpretations of algorithm to tell its story. This is also a hallmark of most tabletop role-playing games (TTRPG). Leaving aside examples of TTRPGs that are designed to be played solo, with the player interacting only with the emergent gameplay of the system, there are countless examples of TTRPGs that pride themselves on collaborative narrative experiences, and the rise of “actual play” TTRPG podcasts and web shows, are emblematic of this. There is a key distinction between TTRPGs that allow for chance to exist within the space and those games that extensively value narrative opportunities created by it. It is a distinction between creative spaces that acknowledge the possibility of chance versus creative endeavors that are both influenced, and, perhaps, determined by the interpretation of chance-based outcomes. In the latter example, rolling a die (or any other chance-based determining element) becomes not only a mechanic of the game, but also the way in which narrative splinters, coalesces, and develops.

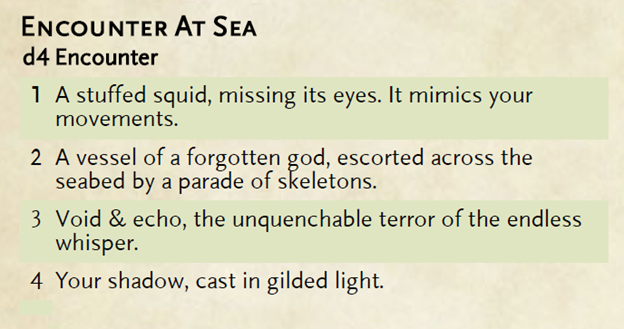

I mentioned at the start of this article that I seek to cultivate spaces in which these chance-based creative excursions can happen, and that’s been true in my most enduring game experience—that of being a Dungeon Master for a 5th Edition Dungeons and Dragons game. This game, which has existed in various forms over the past three years with a consistent group of players, has become increasingly invested in chance as a way of creating narrative. This is especially true as I’ve grown to realize the importance I place on creative collaboration. Part of the way this manifests in the game itself is through random encounter tables in which the characters determine random events in the game.

The current campaign of my D&D game offers a recent example of this. After a previous encounter had resolved itself, I asked a player to roll on a different table, with the result being an experience with a vessel of a long-gone god, carried along the ocean floor by skeletons. A simple enough random encounter but made meaningful through what the players in the game did next—they gave the god a name, a set of worshippers, made it part of their characters’ personal story, and more. That forgotten god was given life by these players and made part of this story that we’re telling together, derived from chance, but unequivocally and uniquely ours.

A question emerges here. Isn’t this just improvisational theater but in TTRPG form? Perhaps, but I think it is more than that. Improv relies on suggestions unknown to the performers, which could be a kind of chance, but the suggestion comes from an audience member who controls that outcome. It isn’t determined entirely by chance. So, to my mind, chance-based collaborative story building is different enough from improvisational experiences to warrant distinction.

But, honestly, maybe that distinction isn’t super important, at least not to the idea of collaborative storytelling being engrossing and entertaining. Because tonight, I’m going to act as Dungeon Master once again, meet up with friends, and we’ll get to work on using this game to build a narrative together. With luck, it will be strange, funny, and maybe a little sad. It will be engaging and surprising. In other words, everything a good story should be.

By Dr. Chris McAllister Williams

Chris McAllister Williams is an Assistant Professor of English and Humanities at UW-Green Bay. He teaches classes in poetry, game writing, and the avant-garde. Along with Dr. Bryan Carr and Dr. Juli Case, he co-directs the Center for Games and Interactive Media.