Mention the name “Justin Bailey” to anyone old enough to remember the original Nintendo Entertainment System and you will most likely get a nod of reminiscence after a brief pause for reflection. You’ll also inadvertently be referencing a significant moment in the history of gender in video games.

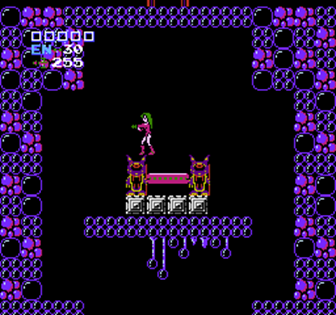

In 1986 (or 1987, depending on what side of the Pacific you were on), players sat down with Metroid, a brand-new game from Nintendo. Unlike the other, more brightly-colored games in the Nintendo catalog, Metroid tasked players with navigating moody, isolated alien worlds as Samus Aran, the toughest bounty hunter in the galaxy, and rewarded them with different endings based on how fast the game was completed.

In the “best” endings – awarded when players complete the game in five hours or less, the game’s biggest twist is revealed. Samus – the faceless, heavily armored warrior that had torn a swath through a cast of alien menaces – was actually a woman, a reveal obfuscated by the use of masculine pronouns to refer to the character in the game’s instruction manual. Half a decade before Chun-Li joined the cast of Street Fighter II’s World Warriors and ten years before Lara Croft became an international sex symbol, Samus Aran was the first playable human female character in a video game – a groundbreaking moment that also served as a predictive microcosm of how female characters are presented in the medium.

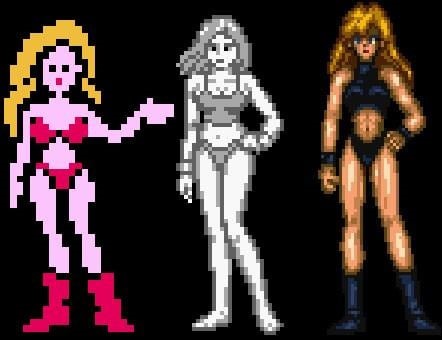

It is not by accident that Samus’ femininity is revealed as a reward to push players to excel – nor is it by accident that her bulky armor gradually strips away the faster the game is completed, all the way down to a revealing swimsuit for finishing the game in under an hour. The way female characters dress – or, to put it differently, how they often do not, is a long-standing trope of the medium and has been the source of significant fan and academic criticism. For many years, it was not uncommon for revealing outfits to be rewards for high-level play or progression (and while it is becoming less common we still see some of this today as well, though the more salacious outfits are now often reserved for paid downloadable content). Such phenomena are a result of the long-standing and only recently-challenged belief that the audience for games is predominantly heterosexual and male, the origins of which go back to toy marketing in the 1980s among other factors and perhaps merit a column of their own. Certainly, the industry’s most prominent female characters are no exception – until a recent redesign made her a more plausible adventurer, Lara Croft was as defined by her impractical short shorts and unrealistic proportions as her gunplay or ability to explore ancient ruins, and Chun-Li’s body was exoticized and fetishized from the beginning.

As it predates these characters and many others that define these tropes, Metroid could be seen as their beginning. In defense of the game, however, Samus is hardly simply an object of player desire. Canonically, she is the most capable and efficient bounty hunter in the galaxy, with a powerful suit of armor and arsenal of impressive weaponry. Metroid creator Yoshio Sakamoto has regularly acknowledged in interviews the significant impact Ridley Scott’s Alien and its heroine Ellen Ripley had on his game, and the similarities are hard to miss. Like Ripley, Samus represents a refreshing feminist perspective on a traditionally male-dominated genre (and in the latter’s case, medium), but where Ripley became an unquestioned pillar of science fiction heroism, Samus’ road has been rockier – and the fact that the JUSTIN BAILEY code (believed to be at different times, slang for a bikini or the name of a particular person but most likely just a random string of code that happens to work) allowed the player to start off with Samus in a skintight leotard instead of her armor further underscored that tension.

Indeed, the series seems inconsistent in how it wishes to handle Samus’ femininity and body. Metroid II: The Return of Samus, a Game Boy sequel released in 1991, has Samus rescue one of the titular Metroid larvae despite her mission to eradicate them, and it believes she is its mother. In 1994’s Super Metroid, widely and correctly considered the best game in the series,she returns the larvae to a space station for safe keeping, only for it to be beset by her enemies looking to use it as a weapon – the creature ultimately sacrifices itself to save her at the end of the game. The idea that Samus must innately become a mother – that this is an inherent part of a woman’s journey – is debatable in terms of its practical and narrative value, as little indication of her maternal instincts had been made in the text of the games (the tie-in comics did at least add some context to her actions). Unlike previous games in the series, Samus’ armor also explodes when she runs out of health – revealing in a split-second explosive flash her scantily-clad body, which emits a shriek just before her death. Whether the player succeeds or fails, they still get to see Samus as objectified:

While most of the games after this tried to recontextualize and desexualize Samus – first-person spinoff Metroid Prime’s best endings merely have her removing her helmet – it was 2010’s Metroid: Other M that represented perhaps the greatest fumbling of her character. While the game received generally positive reviews and played well, it was roundly criticized for its portrayal of Samus. As long-time games critic Jeremy Parish wrote in his helpful postmortem on the game, the character went from a stoic, capable warrior to a “sulky child” who squabbled with her male commanding officer while still seeking his approval and froze up in front of enemies she had fought several times before. More egregious was its change to the game’s progression – while the Metroid formula is built around collecting new weapons and abilities that allow access to previously unreachable areas and items, encouraging player backtracking and exploration, in Other M the hardened bounty hunter had to ask permission from her commanding officer to use new weapons instead of collecting them herself. Unlike most Metroid titles, Other M plummeted in price quickly and is widely considered to be a low point for the otherwise critically-acclaimed series.

Complicating matters further is the Zero Suit, which first appeared in 2004’s Metroid: Zero Mission, a remake of the original game. The Zero Suit acts as the tactical suit Samus wears under her armor and just so happens to be skintight. From a gameplay perspective, Samus is generally a nimbler and less powerful character in this mode, which makes sense as it is not as bulky as her regular armor, and was intended to create more tense situations for players by not offering the same offensive and defensive capabilities. However, the redesign also gave Samus impractically high heels, more exaggerated measurements and a slender frame, and most strangely for a tough-as-nails bounty hunter, makeup. All these changes seemed at odds with her previously established canonical height, weight and body type and led to fan complaints.

The Zero Suit changes carried over to other games as well. Nintendo mascot fighting game Super Smash Bros. Brawl offered the Zero Suit as a toggled option for players to utilize with the regular Samus outfit. However, Smash Bros. For 3DS could not handle having two character models loaded into memory at once and instead made Samus and Zero Suit Samus separate characters. For parity’s sake, this carried over to the more technically proficient Wii U version as well, and was codified as series policy in the franchise-encompassing Super Smash Bros. Ultimate – in these games, the Zero Suit was adjusted even further to give her a sports bra and spandex shorts as an option, leading to further backlash over the perceived objectification of Nintendo’s pre-eminent female lead (non-Princess category).

Earlier this year, Nintendo surprise-announced Metroid Dread, the horror-focused fifth entry in the main (non-spinoff) franchise and the first original non-remake game in nearly two decades. While it remains to be seen what Dread will add to Samus’ legacy, the fact that she continues to endure as a fan favorite – despite her uneven production history – speaks to the character’s significance. Ultimately, despite these ups and downs (which many of her female contemporaries also faced), Samus remains a beloved character, an important part of gaming history, and a crucial incarnation of the discourse around female characters in video games – those looking to study the issue would do well to spend some time with the Metroid series.

Until next time, don’t forget your cybernetic battle armor.

By Dr. Bryan Carr

By Dr. Bryan Carr

Bryan Carr is an Associate Professor in the Communication, Information Science, and Women’s & Gender Studies departments. Among other things, he is the host and producer of “Serious Fun”, a podcast taking an academic look at popular culture on the Phoenix Studios podcast network. He has never been good at Metroid.