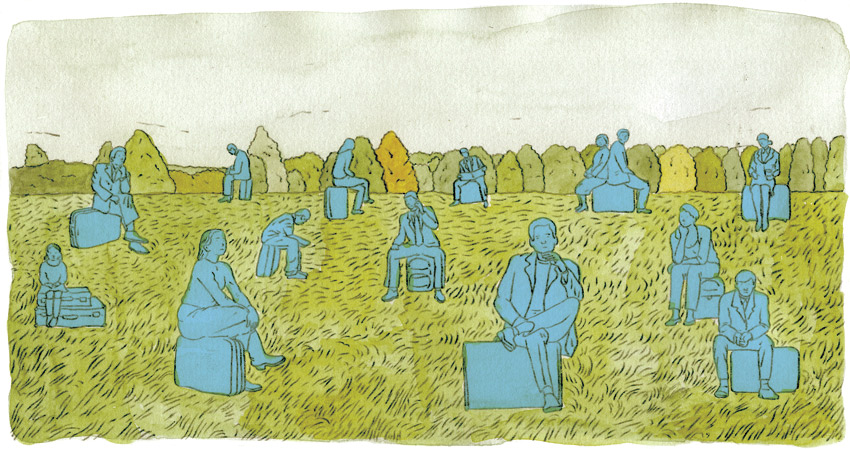

Dr. Alise Coen explains why “there is no single category or simple dichotomy in which “immigrants” can be placed.”

Art by Masha Krasnova-Shabaeva

U.S. voters identify immigration as one of the most important issues shaping their preferences at the polls, and surveys regularly track American public opinion to assess whether immigrants are perceived as strengthening or weakening the country. Among lawmakers, policy impasses over immigration-related issues have threatened government shutdowns, and platforms focused on immigration have been central to election campaign strategies. Despite (or perhaps because of) its polarizing nature, fundamental elements of the U.S. immigration conversation remain blurry or misunderstood. This includes the discussion of “immigrants” as an undifferentiated monolith.

There are many paths to becoming an immigrant in the United States, yet public discourse often sidesteps the nuances of these categories. Lawful immigrant status can be obtained, for example, through family-based, skills-based, or temporary work and education visas (among others). U.S. immigration law places caps on the annual allocation of these visas, and obtaining family-based visas can take over 20 years depending on national origin. A distinct humanitarian category of lawful immigration includes refugees—individuals processed overseas who must meet international legal standards regarding a well-founded fear of persecution. The U.S. President, in consultation with Congress, sets annual ceilings on the number of refugee admissions, and security vetting typically averages 1.5 to 2 years. While conversations surrounding immigration often contrast “citizens” with “immigrants,” many U.S. citizens are foreign-born immigrants who became naturalized after fulfilling eligibility requirements.

In the wake of such category complexities, one trend in U.S. political discourse has been to simplify the parameters of the debate by distinguishing between the overarching typologies of legal versus illegal – those with lawful authorization to be in U.S. territory versus those without. This juxtaposition offers a veneer of moral clarity in which legal immigration is good and illegal immigration is bad.

The legal-illegal dichotomy is more precarious than it sounds. Migrants without lawful status may have entered the country irregularly (via unauthorized border crossings), but many lack lawful status due to visa overstays or other factors. Over three million individuals lack lawful permanent status on the basis of being brought into the country as young children. Policy debates over DACA and the Dream Act forefront questions regarding the extent to which such “undocumented” or “illegal” immigrants ought to be distinguished, for example, from immigrants lacking lawful status due to overstaying visas or irregularly entering the country as adults. Ensuing questions surrounding protection for unauthorized immigrants who have consistently paid taxes, contributed to the labor market, and become proficient in English then emerge. Answers to these questions hinge on interpretations of Americanness, identity, and national belonging, while also tapping into notions of American Exceptionalism as inextricably linked with hard work and economic productivity.

Further challenging the legal-illegal paradigm, international law requires distinct treatment for individuals who have irregularly entered a country’s jurisdiction as asylum-seekers in search of refuge from persecution. Such individuals may lack lawful status due to their desperation in fleeing life-threatening conditions of harm or torture. Conflating this category of migrants with voluntary migrants who are not forcibly displaced not only violates international legal standards but also masks important differences in the circumstances prompting their journeys.

A key takeaway here is that there is no single category or simple dichotomy in which “immigrants” can be placed. Rather, diverse layers of policy questions begin to emerge when moving beyond superficial representations of the immigration debate. Narratives offering simplistic portraits of this debate in U.S. politics often use “immigrants” and the legal-illegal paradigm as political instruments, which is easier and arguably more expedient than grappling with the difficult nuances animating immigration law. But this misses the heterogeneity of who is impacted and perpetuates one-dimensional understandings of a multidimensional policy issue.

By Dr. Alise Coen

By Dr. Alise Coen

Alise Coen is Assistant Professor of Political Science in UW-Green Bay’s Public & Environmental Affairs unit.