When you hear the word “Hollywood,” most people don’t think of the neighborhood in central Los Angeles rather of the movies. In fact, when you google “Hollywood,” you find that it is “a larger-than-life symbol of the entertainment business” that is even immortalized in the iconic sign of the same name in the hills overlooking L.A. How this came to be is a long story, but it dates back to the Golden Age of the film industry and a time (1940s-60s) when large movie studios produced almost all of the films in this country. The studios had long term contracts with all of their creative personnel (actors, actresses, directors, screenwriters, etc) who worked on studio lots and created what came to be known as the classic Hollywood style or what film critics call the dominant style (you can see this era re-created in David Fincher’s 2019 film Mank).

But along with that system came a type and style of filmmaking that had certain genre-specific characteristics. We knew what to expect from a comedy, a drama, a musical, or a film noir. There were certain expectations and cinematic conventions that came along with this style of filmmaking that proved to be enormously popular and influential. European directors in the 1950s and 60s studied these films and learned from them. Ironically, they created a new type of filmmaking, the artist’s film (film d’auteur as it was expressed in French cinema) that at once referenced and copied Hollywood genre cinema yet also played with and expanded its possibilities. These films represented a different kind of work of art in that the director was the creative artist and not just a member of a collaborative. Usually, the director was also the screenwriter (sometimes even editor or cinematographer) and many directors (Godard and Truffaut in France for instance) wrote screenplays for their fellow directors. This enabled filmmakers to express a singular vision without the influence of the studio and executives who often put entertainment and profit ahead of art.

In the U.S., such filmmaking became known as “art house” cinema or, more generally, “independent cinema” in that it was made independently of major studios. As these films became more and more popular, studios took notice, most notably the now disgraced Harvey Weinstein, whose production company Miramax was the darling of the 1980s and boosted many young cineastes to fame. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Steven Soderbergh, Kevin Smith and others, became popular directors whose films garnered both commercial and critical success through the “Miramax treatment” (that included award lobbying). With Miramax’s success, it became hard to define what exactly was “independent” about these films anymore as Weinstein had great influence over many aspects of the production and fancied himself in the tradition of studio moguls of the past.

With Miramax’s demise and the advent of on-line streaming services, smaller “art house” films could now reach new audiences and circumvent the studio system and its distribution arm. This of course called into question what exactly was “independent” about these films. When independent goes mainstream, what about it is new or different? While Hollywood still churns out mainstream, formulaic features (horror, superhero/Marvel films, James Bond, etc)—albeit with new twists and inventions—some of the most inventive and creative work is found in series produced by HBO, Netflix and other streaming services.

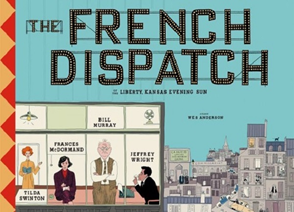

So, what does that mean for creative filmmaking? Is there still an “art house” style when there are so few art house cinemas left? Is there an independent film movement, when the indie scene was long ago co-opted by major studios? I would say: yes and no. One of the things that the major studios did was develop distribution arms that specialize in producing and distributing non-mainstream cinema. To be sure, creative filmmaking never died out, as creativity is the mainstay of art and artistic production. And that brings us to Wes Anderson and his latest creative film offering (playing in Appleton and hopefully soon in Green Bay before it moves to streaming) The French Dispatch. Anderson has developed, one might say, a kind of cult following for his off-beat and visually distinctive style of filmmaking. His fans are passionate about which of his films are their favorites (Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, Fantastic Mr. Fox, the Isle of Dogs, etc.) and why. His films are visually arresting, and noted for their smart soundtracks thereby enabling him to attract some of the top actors and actresses working today (Bill Murray, Frances McDormand, Timothée Chalamet) for productions that by Hollywood standards are low budget, yet gives actors a challenge and the cachet of having been in a Wes Anderson film. By all accounts, The French Dispatch promises not to disappoint and will no doubt be a contender as a fan favorite. Billed as a “love letter to journalists” that takes place in an imagined French city (imagined spaces being specialty of Anderson’s), the film brings to life separate and somewhat eccentric stories published in the fictional journal “The French Dispatch Magazine.” A plot summary never does justice to a Wes Anderson film, as the visuals and the sound are crucial to the cinematic experience. If you’ve never seen a Wes Anderson film or if you’ve seen all of them, do yourself a favor and check out his latest film on the big screen. You’ll be glad you did.

By Dr. David Coury

David Coury is a Professor of Humanities (German) and Global Studies and also Co-Director of the Center for Middle East Studies and Partnerships. Additionally, he is the director of the Green Bay Film Society, whose International Film Series screens international and independent films twice a month at the Neville Public Museum. Admission is free and all films are open to the public.