Introduction

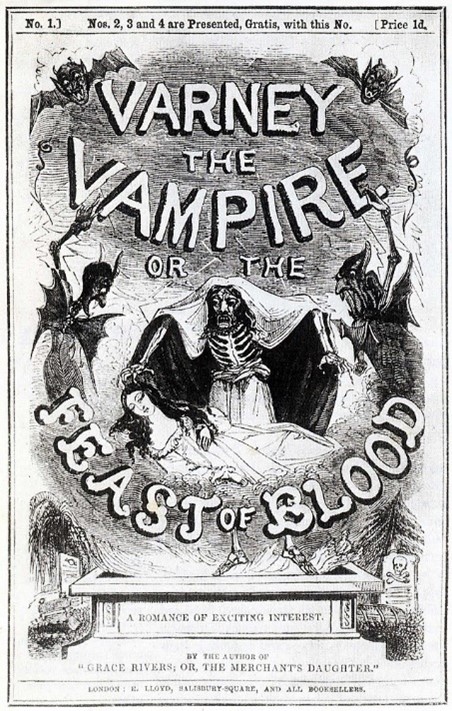

Varney the Vampyre was a story written by James Malcolm Rymer and published in installments between 1845-1847. These installments were called penny parts, because they were distributed for a penny a piece (Cameron 50). Varney the Vampyre became successful due to its imagery, relatability, and affordability. What better way to enjoy the story of Varney than imagining yourself in the shoes of a 1840s working class citizen? After conducting research on this time period in Victorian America, I fabricated a character to whom that I could relate. Below, I will be writing journal entries in the persona of this character, reflecting on chapters one and two from Varney the Vampyre. I hope for this reflection to provide a new perspective on Varney the Vampyre.

The character is twenty-four years old and lives in New York City in the mid-1840s. In this time period, many of the New York immigrants were from Germany and Ireland. My character and her family are immigrants from Germany, placing them as a part of the working class (Wall 104). I chose this as her nationality because I am more than 75% German myself. Their entire family works in a shoe making shop nearby, which was a common profession for New York German immigrants (104). Her husband and his brother are the main workers of the family. However, my character’s five-year old son and nephews also have a full work day. For now, my character remains at home with her two young toddlers. In addition to tending to her children, she does all of the housework. In 19th Century New York City, child labor was an essential aspect of the working class (103). Since their family is of a lower class, they share a single-room apartment with her brother in law’s family. This totals their household number to eleven, soon to be twelve because the character is pregnant. Once my character’s infant is old enough to walk, she will continue helping in the shoe shop. These living conditions were normal for someone of the working class in New York City (Wall).

Sunday, October 5, 1845

This day was both ordinary and extraordinary. Ordinary, due to my daily Sunday routine. It is the Lord’s Day, so my family and all nature is resting with Him.[1] A gloomy morning, but it was brightened in the afternoon.

I was walking up the stairs, bringing with me as much water as I could tote.[2] Water is a necessity, even on the Lord’s Day. Once I reached the top, all tuckered out, my husband was waiting to receive the water from me. Thank the Lord for my respectful husband. After I handed him the water, he mentioned that he had brought back a surprise for the family. I was naturally curious, but he would not utter a word until we reached our home.

Once we opened the door, I was greeted by my children and nephews. They were excitedly waiting for my husband to share his secret surprise with us. It turned out, he had bought us the first chapter of a new novel! Oh, I love stories. They are a distraction from the hardships and struggles. He explained that it only cost a penny per issue, and he had brought us the first one.[3] We were eager to hear this story, and he obliged our wishes. My husband sat down in a wood chair and pulled out the story. As we all found our seat on the ground, my young daughter crawled into my lap.

He began reading the tale. Varney the Vampyre was its title. My husband reads stories in such a lovely way. He lowered his voice for the ominous parts, added pauses for suspense, and talked louder and quicker for the action. Later in the night, he told me that it brings him great joy to read to his family.[4] He says that our reactions make the story more interesting.

[1] In 19th Century New York, the majority of citizens were Protestant Christian (Wall 103).

[2] The working class did not have any domestic help, and were tasked with carrying up their own water, normally up several flights of stairs (Wall 109).

[3] (British Library Board).

[4] At this time period, there was a push for social reform in marriage. In families, men were honored by society if they spent time with their wives and children. The ‘family man’ was the goal for most men (Cameron 50).

The first issue of this story was quite gruesome. It consisted of an attack on a helpless woman by a vampyre. The vampyre is a terrifying creature. He acted all possessed, with his bloodless face and fanged mouth. It was said that “the glance of a serpent could not have produced a greater effect upon her.” What could be more terrifying than the serpent himself? Surely it was the work of the evil one, who must have grasped onto the poor woman.

I was left with a feeling of uneasiness. The woman was treated very disgracefully. The vampyre dishonored the woman when “her bed-clothes fell in a heap by the side of the bed.” This implies that her purity was stolen from her.[5] What an unspeakable action. Instead of dwelling on this, I choose to examine the imagery in the story.

It is undoubtedly a peculiar story so far, yet it kept my attention throughout the whole chapter. The author, whoever he may be, certainly had a talent for setting the scene. I was surely captivated by the description of the beautiful woman. As I write this journal entry with my right hand, the first number of Varney the Vampyre is in my left. From it, I draw this quote: “Oh, what a world of witchery was in that mouth, slightly parted, and exhibiting within the pearly teeth that glistened even in the faint light that came from that bay window. How sweetly the long silken eyelashes lay upon the cheek.” What a beautiful and detailed description of the young woman. The author painted a picture in my mind with words, better than any painting I have ever seen.

How I wish I could attain the next issue immediately. I am unsure if I will be able to stand waiting a whole week. At least something will entertain my mind over the next week.

Is the woman dead? Surely, she must be. But how will the story continue without her?

Until later.

[5] At the time “Varney the Vampire” was published, there was a movement to end sexual impurity, especially concerning women (Cameron 49). A reader in 1840s America would be uneasy at this implication of Flora being sexually assaulted.

Wednesday, October 8, 1845

It is not yet Sunday, so I have not received the next issue. Nonetheless, I have many thoughts plaguing my mind. Varney the Vampyre has been in the back of my mind all week. While I stitch closed the hole in my husband’s shirt, I wonder about the woman. While sweeping the floor, I ponder who will come to her rescue. Will her family find her cold as a wagon tire, bleeding out in their sight? Overall, I ask myself: what will happen next?

I allow that I should not be worrying of such things. Such fictional things. Mind, I still permitted my mind to wander back to the story. Sakes alive, I even read the story to myself a few more times.

Upon examining the story further, I am even more nauseated by the fashion that the woman was treated.[6] Not only was the scene sickening from the gore, but I continue to wonder whether it was indeed an invasion of her chastity. It is shameful that I am pondering this issue so much, but I sympathize with the character. I can envision myself in a similar situation to this woman. We are similar in that we are both of the more delicate gender. I imagine that I would be helpless in her situation, being taken advantage of in that way. Even in my marriage, my husband does not treat me so vulgarly.[7] Since I am unfamiliar with this type of violation, I am unsure what action I would take if I was the woman in chapter one. I assume I would do the same as she did: I would call upon the help of the Lord.

I admire the way that she prayed when she was in fear. When a storm raged outside and she heard strange sounds, “to the great God of Heaven she prayed for all living things.” I wonder if the woman survived the attack. Although it seems unlikely that she would survive, I would assume that the Lord would come to her aid in her hour of need.

The whole scene caused my nerves to be all-overish. The attack on the woman made me unconsciously more cautious. These past few days, I have been jumping more at strange sounds. It is not simply the vision of the vampyre that is frightening me. It is the actions that he inflicted on the woman. When my husband is at work, I pray that no one will come into our home. After all, there is only myself to protect the young. The wind on Monday night caused me to turn. Some nights, I lay in bed and wonder if our rusting lock will hold the door closed. I do not tell my husband, as he would likely consider my mental health as failing.[8] It is not natural for a woman to worry over such things, yet I continue to do so. Why? I assume it is the lack of closure. The ending did not satisfy my mind. I wish I could know what has happened to the woman. Perhaps I will learn of her name in the next issue.

Until later.

[6] Varney urges the feeling of repulsion in the reader, in the way he attacks Flora (Cameron 48).

[7] There was an ideology that became popular: men do not have complete control over their wives’ bodies. It was seen as healthy for women to enjoy sexual behavior, as it is important for a man to (Griswold 732).

[8] Advances in technology from 1830-1850 led to a change in care for the mentally ill. More people had the need for care, so there was an expansion in insane asylums. (Morrissey & Howard). This increased fear in women, who were often falsely categorized as mentally ill.

Monday, October 11,1845

At last, the next issue of Varney the Vampyre has entered my grasp. My children and I have been waiting the whole week for this indulgence. We did not receive it yesterday, but my husband brought it home today. Today, I will not bore myself with writing about my day. I will go promptly to the topic on my mind: the story.

This author sure enjoys when his readers are left to wonder to themselves. Again, the chapter was left unfinished. “I have shot him” is the final sentence in issue two. What does this mean? Is the monster dead or alive? For Flora’s sake, that is the woman’s name, I hope that the monster has been slain. ‘An eye for an eye’ is not a Christian teaching… Yet I believe, in some cases, it is necessary. A life for a life. Poor Flora’s life was no less valuable than the powerful vampyre’s.[9]

In truth, I wonder if Flora’s life was more valuable than her attacker’s. After all, humans should be valued over mere animalistic creatures. The vampyre does not seem to be very human-like. I wonder if it has more correlation with the evil one. Its description was assuredly like an animal: “the eyes had a savage and remarkable lustre,” “a strange howling noise came from the throat of this monstrous figure,” and it had “large canine looking teeth.”

My husband eyes me anxiously as I write these quotes in my journal. Perhaps he believes me to be too invested with this story. He may be right, I have housework to continue. If I feel inclined to ponder the story more, I will ask my son what he thinks. He has a brilliant mind for a child.

Until later.

[9] In the 1840s, the first significant women’s rights movement took place in America. Previously, men were considered more valuable than women. However, in the early 19th century, women were pushing for equality with men, both socially and politically. Many women latched onto this ideology in the 1840s (Parkerson 164-165).

Conclusion

After these two chapters, I believe that my character would continue to reflect over Varney the Vampire in journal entries. She would write about other stories that became popular within the working class. Potentially, this character may write more forms of intriguing literature analysis. Especially when her children are adults and she has the time to reflect; spare time is slim and valuable to the working class. After her children were slightly older, she would need to continue to work, as did many of the working class in New York in the 1840s (Wall 103).

As my character continues to read Varney the Vampyre, she will relate herself to Flora. They are both women who are living around the same time period. My character will both pity and envy Flora. She will pity Flora due to her situation with the vampyre and the way she is treated by her brothers. However, my character will inevitably envy Flora’s wealth. My character grew up in the working class, so she would long for the life that Flora had lived.

Also, the further issues of Varney the Vampyre would cause her to ponder the societal reforms that took place around her. Ultimately, Rymer intended Varney the Vampire as a response to several social reform movements in the 1840s (Cameron). In the United States, there were several of these reforms happening in the 1840s. Some included movements against alcohol, slavery, colonization, and women’s oppression (National Geographic). Although these were issues for the middle class to handle, many of the working class would be hearing of them as well. They became popular gossip on the streets of New York. Since Christianity was a large influence in America, it also encouraged people to follow these social reform groups (Parkerson 161). This caused social reforms to target people’s religious morality, not just political standing. Rymer criticizes the class system in Varney the Vampyre. Readers, such as my character, would reflect on the negative effects of the class system. My character may write about her thoughts on this in her journal. Most likely, she would also criticize the class system in New York. She was heavily affected by this unfair system. According to Parkerson, in the early 1800s, the wealth in New York was distributed unequally, with 1 percent of the population owning 40 percent of New York wealth (166). After my character read Varney the Vampyre, she would recognize her economical situation and feel disrespected and restricted. Cameron reflects on this topic and states that “gothic penny fiction also appealed to working-class readers who saw themselves in similar stories of disenfranchisement and exploitation” (Cameron 52).

In addition to the class system, another large theme that Rymer discusses is love. Eventually, in Varney the Vampyre, Varney pursues Flora romantically. Although, my character may not render it romantic in her journal entries. In the 19th century United States, there was an age of reform for marriages as well. Americans began to prioritize romance and affection in households, including compassionate marriage (Griswold 722). This was due to the example led by the upper and middle classes. These higher classes provided the working class with a marriage model; there was a push for marriage to be consensual for both parties, the male and the female (Cameron 49). The relationship between Flora and Varney resisted the new view on marriage. Instead of being a loving suitor, Varney was quite forceful and unaffectionate according to the new standards in the 1840s. My character would later write about her disapproving views towards this pairing. Also, she may compare her own marriage to the relationship of the characters in Varney the Vampyre.

As I predicted, I benefited from researching the time period and societal reforms in the 1840s. One particular source, A Nineteenth Century Slang Dictionary by Hadley, allowed me to use words and phrases that were authentic to the time period. When writing through my character, I was able to experience Varney the Vampyre in a whole new way. Instead of relating the story to my own experiences, I was able to connect it to a whole new perspective. By placing myself in Rymer’s time period as an American, I could clearly see the connections between Varney the Vampire and 19th century societal issues.

Bibliography

The British Library. (n.d.). Varney, An Early Vampire Story. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/varney-an-early-vampire-story.

Cameron, Brooke. “Domestic Plots and Class Reform in Varney the Vampire.” Victorian Popular Fictions, 4, no. 2 (2022): 47-62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.46911/VJXP7684.

Griswold, Robert L. “Law, Sex, Cruelty, and Divorce in Victorian America, 1840-1900.” American Quarterly, 38, no. 5 (1986): 721–45. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2712820.

Hadley, Craig. A Nineteenth Century Slang Dictionary. http://mess1.homestead.com/nineteenth_century_slang_dictionary.pdf.

Morrissey, Joseph P., and Howard H. Goldman. “Care and Treatment of the Mentally Ill in the United States: Historical Developments and Reforms.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 484 (1986): 12–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1045181.

Parkerson, Donald H. “The Structure of New York Society: Basic Themes in Nineteenth-Century Social History.” New York History, 65, no. 2 (1984): 159–87. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23173231.

Wall, D. DiZerega. “Examining gender, class, and ethnicity in nineteenth-century New York City.” Historical Archaeology, 33, no. 1 (1999): 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03374282.