This Friday (presuming no cataclysmic network outage and hoping CAHSS and Effect didn’t decide to finally revoke this column) sees the release of the mildly-anticipated new blockbuster video game, Square-Enix’s Marvel’s Avengers. The title, which frankly could have used one more trademark, plops the bankable superheroes into the midst of a cooperative online action role-playing game that tasks players with fighting against waves of supervillains and their minions to collect better loot for their heroes that cannot change or be reflected on your in-game character in any way.

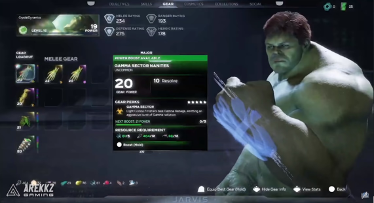

It’s a dream come true, if your dream is finding improved forearms for the Hulk.

As someone who loves superhero comics and loot-driven games where you defeat waves of enemies to get improved gear that lets you beat tougher waves of enemies to get better gear, this sounded like a layup. But the beta left me cold – I didn’t feel like I was playing as some of my favorite comic book characters, I felt like I was simply pushing the buttons on the Skinner Box to make numbers go up and things fall out of the interchangeable bad guys. I was playing as Ms. Marvel on the screen, but ultimately it could have been anyone doing those rote actions and making meters fill up. I even went on a Twitter rant about it.

Maybe these issues are resolved in the full game, though this close to release it seems unlikely that any major changes can be made. But the experience got me thinking – from a design standpoint, what makes a good superhero game? More than that, can you reduce it to basic elements that should be included? It seems easy, but history is littered with many attempts that fell woefully short and some that never even got made.

For the purposes of this article – because this particular intersection of my interests could fill an entire book if I really sat down to think about it – I identified three major from my armchair perspective: action, tone, and roster.

Action

As an art-driven medium with roots in two-fisted pulp fiction, the superhero genre is defined by its focus on action – specifically the kinetic movement of bodies through space, explosive battles and feats of strength. Of course it’s not all punching and flips – there’s more to it than that, in the best of examples – but superheroes are defined in part by the ability to do things normal people cannot in ways unique to their power set.

Similarly, the act of game design is in part teaching players how to take certain actions in particular situations to best a challenge put in front of them. In an article for games industry site Gamasutra, designer Daniel Cook breaks game design down into a simple concept called “skill atoms”, in which the player learns what actions lead to which simulations and the feedback the game presents to the player as a result – over time, these simple skills are linked together to form more complex interactions. Think about how you learned how to walk – one foot in front of the other, balancing. Then, as you became more confident, you were able to run, and jump, and get a running start to jump further, and then judge distances to see if you could jump across them.

Of course, being a superhero is different – how do you swing across buildings as Spider-Man or use all of Batman’s gadgets and martial arts skill? In 2018’s Marvel’s Spider-Man, developers at Insomniac built on the long history of physics-based swinging in previous games (particularly 2004’s excellent Spider-Man 2) by breaking down the complex act of swinging into skill atoms and button presses, allowing them to quickly and simply explain to players how holding certain buttons associated with certain actions – swinging, jumping, etc. – allow the player to accomplish the goal of being Spider-Man:

As the player learns how to use these simple concepts of swinging, detaching, and jumping at various heights and momentum to build speed and different angles of approach and slowly starts to add other abilities (like the point-to-point zip-line), it becomes second nature to zip around the city with speed – even for an uncoordinated dork like me.

Tone

Every superhero has a distinctive tone and aura around them, honed by decades of writers and artists contributing to a larger monomyth. The best superhero games are designed specifically around their lead characters, creating situations and stories that only they could really experience. The idea of game “aesthetics” is often thought of solely at a sensory level – how does a game look, or sound? – but aesthetics go deeper than that – as Simon Niedenthal suggests, aesthetics also extend to how a game feels to play or what sort of experience the player has with it. Superhero media are a dime a dozen – prior to the COVID-19 shutdown, you couldn’t throw a rock at the theatrical release schedule without hitting a blockbuster film based on another formerly obscure character – but games are unique in that they can create the sensation of being that hero, and the aesthetics that shape that experience contribute a great deal to the tone of the game.

Consider 2009’s Batman: Arkham Asylum, widely considered to be one of the best superhero games ever made. The tone is set early on, with Batman bringing the Joker to the gothic, borderline eldritch grounds of Arkham Asylum. As chaos inevitably grips the prisoner transfer, locking Batman and his greatest villains inside, the player becomes Batman not just in avatar form but in spirit. While a great deal of the game centers on Batman’s formidable fighting skills – with combat that supposedly began life as a rhythm game – the player also spends a great deal of their time in the world skulking around the shadows, preying on the “cowardly and superstitious lot” through careful stealth and quick, targeted takedowns that make him less a superhero and more like the Predator. This, combined with the dark color palette of the game’s visuals and the focus on psychological manipulation and terror (including particularly inspired sequences where Batman is under the effects of the Scarecrow’s fear toxin), creates a game that is tonally perfectly matched to the source material, as opposed to many earlier Batman games where he simply walks to the right and punches guys.

Another wildly successful superhero game, 2005’s Hulk: Ultimate Destruction, took a different tonal approach – focusing on the Hulk as a raging id for the player. As my former colleague Ben Geisler, who worked as a Lead AI Programmer on the game, told me, the development focused primarily on the Hulk’s tremendous strength, ability to turn everyday objects into weapons (including smashing cars into ersatz boxing gloves), and “grand scale boss battles” all designed to show off the character’s unlimited destructive power. In short – they designed the game around the character, rather than trying to shoehorn him into a different design. The end result? A game that is considered to be one of the best superhero games of all time. Sometimes boiling down to the essence of a character – getting that tonal quality right in terms of the story and the action – is all it takes to make a successful game.

ROSTER

The superhero genre is a vast, sprawling place. Many characters have close to a century’s worth of continuity to keep up with, with various levels of canonicity and countless arcane character relationships, events, retroactively changed material – now multiply that by the fact that DC and Marvel have thousands of heroes each under their own respective umbrellas. Mastery and memorization of all of this pop culture ephemera is almost part and parcel of the fandom – both companies maintain thorough online databases of their characters, all-encompassing tomes like The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe are cherished parts of many fans’ bookshelves, and as a kid I fondly remember collecting trading cards with heroes and villains that I knew and countless others that I didn’t.

Games like Marvel: Ultimate Alliance, the Lego Marvel and DC games, and mobile titles like DC Legends and Marvel Future Fight allow the player to collect (and in many cases purchase) a full roster of their favorite heroes. While they may not have the bespoke tailoring of gameplay around them like the more singularly focused titles, there’s something undeniably compelling about collecting virtual recreations of your favorite characters and assembling them into dream teams. I can make an all Spider-verse team in Ultimate Alliance 3, unlock costumes and gear for a deep roster of my favorite DC characters in Injustice 2, or put together teams based on cute jokes and puns in Future Fight. It’s just like flipping through the handbooks or wikis or collecting action figures and trading cards – the gathering of your favorite heroes is part of the fun, and the deeper the bench the better. To borrow a phrase from another series: part of the fun is catching ‘em all.

In that light, it’s not surprising to learn that the decision to make Spider-Man a console-exclusive hero for the PlayStation version of the new Avengers game (meaning he will not appear in the game on any other platform) has led to a great deal of controversy and frustration. Not only does the decision keep an entire body of fans from being able to play a distinct character in the game, it also flies in the face of the fun of these superhero team-ups – having a growing and expanding collection of heroes that you can choose from to re-create your favorite collaborations and moments.

SEND UP THE SIGNAL

The superhero genre is a perfect one for video games, with its colorful characters and incredible feats translating perfectly into experiences that can empower players. However, that license is only as good as the design it’s attached to – just slapping a Wonder Woman model in a generic action game doesn’t automatically make it better. Instead the game should be developed around what these characters can do and what makes them unique in the realm of fiction.

Until next time, don’t tug on Superman’s cape.

By Dr. Bryan Carr

Bryan Carr is an Associate Professor in the Communication, Information Science, and Women’s & Gender Studies departments. Among other things, he is the host and producer of “Serious Fun”, a podcast taking an academic look at popular culture on the Phoenix Studios podcast network. He is thankful that superhero games exist so he can pretend to be Spider-Man without doing any damage to himself or surrounding property.