Every year, on the first Monday in September, Americans celebrate Labor Day. Most readers probably associate it with barbecues, long weekend vacations, and the unofficial end of summer.

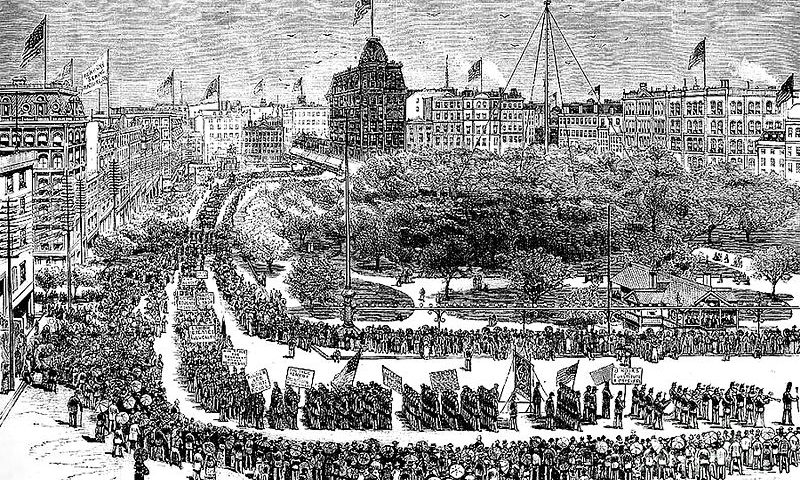

Few Americans, however, spend much time reflecting on the reason for the holiday. Its origins, in fact, date back to 1882. In the first “Labor Day parade,” organized by unions in New York City, workers used the occupation of physical space to demonstrate their collective power. Twelve years later, Congress made the day an official holiday. Of course, Labor Day marks a celebration of the overall contributions of working people in the US, but more importantly, it signifies the ongoing struggle of workers to improve wages, conditions, and rights on the job.

Indeed, in the era in which Labor Day was forged—historians call it the “Gilded Age” to mark the conflict over who would benefit from the massive amounts of wealth that were created during the second industrial revolution—employers fought hard to keep wages low and to avoid responsibility for dangerous, unsafe, and tedious working conditions. Many of the basic standards for our workplaces that we now take for granted—a forty-hour work week with a two-day weekend, employer-sponsored health insurance, a minimum wage, and workplace safety, among many others—only happened because American workers who came before us fought for them.

The story of American labor history is extremely rich, and there is enough important material to comprise entire courses of study (such as the course I offer each spring entitled “US Labor and the Working Class: Past and Present”!). Some moments particularly stand out, however, and here are five key turning points in American labor history on which it is especially worth reflecting this Labor Day:

1886: The Strike for the Eight-Hour Day

In the late nineteenth century, there was no standard of an eight-hour work day. Employers often expected workers to work ten, twelve, or even more hours, six days a week. For decades, workers across the US had been organizing to force employers to acknowledge their right to an eight-hour work day, leaving eight hours for rest and eight hours for leisure. In 1886, unions led strikes in cities across the US for the eight-hour day. Though a few were successful, the most spectacular efforts would be defeated in the immediate term. In Chicago, police attacks on striking workers at the McCormick Reaper Works and a bomb that killed several police officers at Haymarket Square led to violence and a wave of repression of militant workers. In Milwaukee, Governor Jeremiah Rusk ended the strike by ordering the state militia to fire on workers in Bay View, killing seven people, including a thirteen-year-old boy (the Wisconsin Labor History Society holds a well-attended commemoration every year). Though the strikers lost, the efforts for the eight-hour day only increased over the years, finally enshrined as the standard once and for all in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

1911: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

Women garment workers in New York City were at the heart of the push for labor rights in the early twentieth century. Feminist labor organizers like the Ukrainian-born Clara Lemlich led the “Uprising of the Twenty Thousand” in 1909, a sector wide strike that forced many employers to agree to higher wages and better conditions. Tragically, however, the Triangle Shirtwaist factory showed that conditions were still extremely dangerous. Many workers continued to toil in prison-like conditions there (exits were locked to prevent worker theft), and when a fire broke out in 1911, 146 workers—most of them young, immigrant women workers—lost their lives. These workers did not die in vain, however, as the state of New York instituted a commission to find out what had gone wrong. Progressive reformers Robert Wagner and Frances Perkins both served on the commission that would recommend factory reforms, and they would later go on to spearhead landmark legislation during the New Deal. Wagner authored the National Labor Relations Act (1935), for instance, while Perkins, the first female cabinet secretary in American history (significantly, she headed the Department of Labor), drafted the Social Security Act (1935).

1935-36: The National Labor Relations Act—and Workers Taking Action

In 1934, a wave of strikes in the United States—among other places, in Minneapolis, in San Francisco, and in Wisconsin, where the Kohler Company’s hired deputies fired into a crowd of strikers, killing two workers—underscored the continued importance of the “labor problem” during the Great Depression. In 1935, Senator Wagner shepherded through Congress the landmark law that established workers’ rights to elect their own union representatives, to collective negotiations with employers, and to go on strike. Many employers continued to resist unions, however, and it took even greater militancy, from the United Auto Workers in Flint, Michigan, for example, who occupied the General Motors plant for 44 days, to get many corporations to agree to bargain. The percentage of workers represented by unions exploded from just over 10% percent in 1929 to 35% by the early 1950s.

1968: Martin Luther King and the Sanitation Workers Strike

Most Americans remember civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. for his famous speech at the March on Washington in 1963, but not as many American recall the purpose of one of America’s largest mass demonstrations. The march, subtitled “For Jobs and Freedom,” was organized by the labor leader A. Philip Randolph, who had argued for decades that only good union jobs would ensure full citizenship for blacks.

Further, many Americans recall that King was in Memphis when white supremacist James Earl Ray murdered him, but fewer remember what King was doing there. In fact, King had come to Memphis to draw attention to the struggle of the city’s sanitation workers, who were poorly paid and toiled in extremely unsafe conditions. The immediate reason for the workers’ walk-out, in fact, was the unsafe equipment that killed two of their own. King and the sanitation workers, therefore, were fundamentally fighting for economic justice as they sought to end white supremacy in the city. Though a heinous act tragically ended King’s life, the city’s sanitation workers won recognition of their union, wage increases, and major improvements of their working conditions.

2018-19: The Teacher Uprising

We are quite likely living through a major moment in labor history right now. For decades, teachers across the United States have seen their salaries stagnate and their jobs become more difficult as they are asked to do more with less. When teachers in West Virginia walked off their jobs in February 2018—in defiance of the law—they drew on a vast reservoir of labor history in the Mountain State, including a long history of vicious attempts by coal companies to stop workers from unionizing.

But the West Virginia teachers also drew on recent educator activism elsewhere: the Wisconsin uprising in 2011, for instance, which represented a massive action against a bill that took away meaningful collective bargaining rights for most public employees in the first state to guarantee them, and the Chicago teacher strike in 2012. West Virginia teachers won a pay increase and the promise of an improved health insurance system, and teachers across the country—in Kentucky, Arizona, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Colorado, and California—have followed suit, seeking raises, more sustainable education funding, and lower class sizes for students. This wave of strikes made 2018 the most militant year for workers in over thirty years. In a Labor Day commemoration in the distant future, historians may very well be highlighting teachers’ activism over the past two years as a major turning point in American history.

By Dr. Jon Shelton

Jon Shelton is associate professor of democracy and justice studies at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. His book, Teacher Strike! Public Education and the Making of a New American Political Orderwas the winner of the 2018 First Book Award for the International Standing Conference of the History of Education. He is also a 2019-20 Postdoctoral Fellow of the National Academy of Education.