I do a lecture on horror movies in my Psychology of Emotion course, and I always ask my students the same three questions to start it out.

- Do you like scary movies?

- If you do like them, have you ever seen one that you found so disturbing, you didn’t enjoy it?

- If so, why was it so disturbing to you?

The answers are pretty consistent. About 70% of my students say that they like scary movies, and almost all of them will say that they have seen one that was just too scary for them.

On the surface, that appreciation of horror movies is sort of a strange phenomenon. It’s not unlike visiting haunted houses or riding amusement park rides. As a general rule, people don’t like being scared so why would they intentionally invite a seemingly negative feeling state into their lives?

There is actually a pretty good answer to that question, but first it’s interesting to explore how horror movies do the work of scaring us.

Horror is a massive genre in film with an average of between 10 and 20 major horror films coming out each year (and a bunch of other smaller productions coming out too). So it’s difficult to talk about how they work on a grand scale in that there will always be some significant outliers. As a general rule, though, horror films use four primary strategies to scare us.

1. First, they capitalize on our innate fear responses. They do this in two ways. The easiest is the “jump scare.” Sudden, loud noises startle pretty much everyone. There are some tricks to it, though, in that we will startle even more if we are already on edge. So they put us on edge via ominous music, darkness, and uncertainty. Imagine, for example, if you were walking down a busy hallway and I jumped out at you and made a loud noise. It would probably scare you, but not as much as if you were walking through a cemetery late at night and I did the same thing. That’s because the cemetery situation capitalizes on quite a few other innate fear responses. Darkness, isolation, and death are innate fears, linked to our evolutionary history. Horror movies capitalize on quite a few of these evolutionarily baked-in fears like animals and other creatures (Jaws, Cujo, Arachnophobia, The Birds), heights (Vertigo), strangers (The Purge, Strangers), and others.

2. Second, they capitalize on culturally relevant fears of the time-period. There’s a reason why zombie and vampire movies have been so popular for the last decade. It’s that they capitalize on our collective fear of viral outbreaks (e.g., Ebola, Bird Flu, Swine Flu). Now, I can hear people saying “wait a minute, Ryan, zombie movies have been popular since the 50s.” That’s true. They have been popular, but if you go back and watch Night of the Living Dead (which is honestly one of the best movies of all time), you’ll note that the zombies emerge from a prominent source of 1950s and 60s collective fear… radiation poisoning (which also brought us other creature and monster movies in the 50s and 60s). Similarly, we’ve seen a number of eco-horror films (The Happening, Piranha 3D, Crawl) and disaster films (2012, San Andreas) since the late 90s that capitalize on the collective fear of environmental destruction and climate change. Finally, some have even pointed to the rise of slasher movies in the late 70s and 80s (Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween) as resulting from on a distrust of authority that stemmed from the Watergate scandal.

3. It’s not just the culturally relevant fears they take advantage of; it’s also the fears of the target audience they prey upon. The primary audiences for horror films are adolescents and young adults (there’s an entire line of research into why older people like me who once loved scary movies tend to turn away from them in midlife). To help their audiences connect with material, they build the plots and locations around common adolescent and early adulthood experiences. Victims and protagonists are often babysitters (Halloween, When a Stranger Calls), camp counselors (Friday the 13th), etc. and venues are often high schools (e.g., Scream, I Know What You Did Last Summer), colleges (e.g., Scream 2; Happy Death Day), or even new homes (e.g., Paranormal Activity, Poltergeist). Meanwhile, the protagonists are often engaging in the common activities of those age groups like studying abroad (Hostel), partying (Jaws), or having children (The Omen, Orphan).

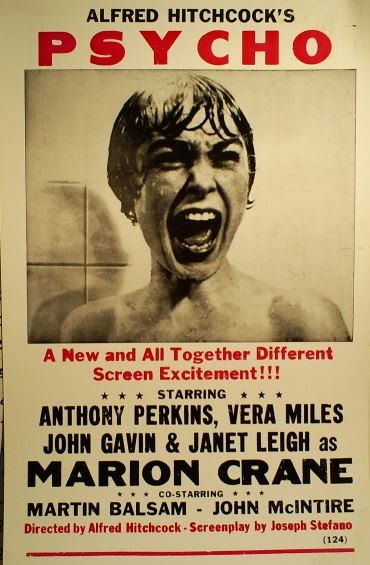

4. Finally, they try to build in to the story a clear invasion of privacy and safety. Victims are often targeted in places where they are vulnerable but feel safe like showers (Psycho) and bedrooms (A Nightmare on Elm Street). They set them in so-called “safe” suburban areas (The Purge, Halloween, Scream) and include a variety of setting shots to remind people that their perceived safety isn’t real safety. Elm St. starts to feel like every suburban street. Related, I’ve actually been listening to a podcast about Halloween this week (In Myers We Trust) and I was reminded of how many victim point-of-view shots there are in that movie (the infamous closet scene is a great example of this). These point-of-view shots have the effect of putting us in the place of the victim and making us feel even more vulnerable. It’s no longer happening to the person on screen. It’s happening to us.

So, back to the questions I started with: Why do people like scary movies and when don’t people like scary movies?

The answer to the first question, why do people like scary movies, is because they are able to cling to the fact that in that moment they are safe. It’s the feeling of fear without the actual threat to their safety. And the reason why one person can enjoy a scary movie and another person can’t is usually because the first person can disconnect and hang on to the fact that it isn’t real in ways the second person cannot. This is demonstrated by the fact that when you ask people who like scary movies to talk about the ones that scared them too much, they usually say those movies were too close to home or too real. They couldn’t disconnect.

If you want more, I talked about this with Jason Cowell and Sammy Alger-Feser on a LIVE episode of Psychology and Stuff.

By Dr. Ryan C. Martin

Ryan Martin is the Associate Dean for the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences and a member of the Psychology Department at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. He researches anger, manages the blog All the Rage, and teaches courses on mental illness and emotion. Follow him on twitter at @rycmart or All the Rage on Facebook.