Happy Birthday, Roald Dahl! On September 13, 1916, Roald Dahl was born in Cardiff, Wales. His parents, Harald and Sophie Dahl, were immigrants from Norway. He would grow up to write much-loved and macabre novels for children including The Gremlins, James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, and, of course, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and its sequel Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator. To many readers, these books might seem very different from traditional “children’s literature,” as they feature raging beasts, tyrannical humans, fearsome monsters, and, above all, violence or the threat of violence. There is even a lively and long-standing fan theory that in Charlie the Chocolate Factory, the chocolate magnate Willy Wonka murders the four children who misbehave in his chocolate factory and are ejected from their prize tour. (In the published version, they reappear at the end, traumatized and deformed but alive and sent home with truckloads of chocolate.) This interpretation turns Dahl’s beloved children’s tale into a work of horror.

However, that might be the most traditional thing about it.

That’s because children’s literature used to be full of horror.

Originally, children’s literature wasn’t intended to entertain. Instead, its authors tried to acclimate children to a strict and dangerous world. Prior to the medical advances of the twentieth century, gradually produced by the scientific and industrial revolutions, infant mortality was extremely high. According to the United States Census, in 1900, one hundred and sixty-five children per thousand listed died in infancy: a mortality rate of over ten percent. How could children be expected to understand and accept this situation?

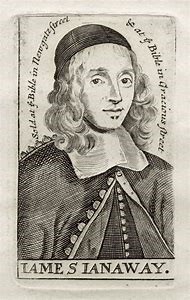

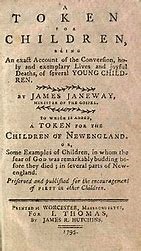

Enter James Janeway. In 1671, this English minister, the leader of a Puritan congregation in the London suburb of Rotherhithe, published A Token for Children: Being the Exact Account of the Conversion, holy and exemplary Lives and joyful Deaths, of several Young Children. Only a few years earlier, in the mid-1660s, Janeway had witnessed the suffering and death of thousands when the Great Plague swept through London and its environs. In A Token for Children, he confronts the death of children from the plague and other diseases that are generally preventable today. “In an ecstasy of holy triumph,” concludes an indicative tale, “she went to heaven when she was about twelve Years old.” The book became a runaway success. Far outlasting Janeway himself, who died of tuberculosis only two years after its publication, A Token for Children remained in print, in Britain and the United States until at least 1875, during which time it was the most popular work of English literature for children excepting John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. Its influence may be found in the dying speeches of several children in Dickens’s novels, including Charles Darnay, fils (A Tale of Two Cities), Paul Dombey (Dombey and Son), and, famously, Little Nell (The Old Curiosity-Shop).

A catalogue of the “joyful deaths” of pious children might seem like a horrific premise for a children’s book, but I think Janeway’s appeal lay to some extent in his genuine belief that children inherently have human dignity. One child protagonist is “highly awakened” by a sermon that she comprehends better than her parents do. Another is an independent critical reader. “Her book was her delight,” Janeway claims, “and what she did read, she loved to make her own,” commenting on it “with extraordinary observation.” Clearly, Janeway considered children full human beings, not simulacra or possessions of their parents.

In showing children how they ought to behave, A Token for Children is an early contribution to the genre of conduct literature, or “how to” books focused on etiquette, manners, and civility. Not all eighteenth and nineteenth century conduct literature was written for children. In fact, quite a lot of it instructed young women on how to be good daughters, domestic servants, and wives. Two of the earliest English novels fit this description: Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded (1740) and Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady (1748). However, some of the most popular children’s literature titles were conduct literature.

Eventually, some writers got sick of reading about the deaths of holy children, and started to push back. William Godwin, philosopher, political activist, novelist, and father of Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, was horrified by Janeway’s Token during his own childhood—possibly on account of the infant deaths of several of his siblings—and, with his second wife Mary Jane Clairmont Godwin, founded The Juvenile Library, a press that specialized in Enlightenment-informed children’s literature. One of the Juvenile Library’s publications was The Swiss Family Robinson, the first English translation of Johann David Wysss’s 1812 classic Der Schweizerische Robinson.

Another nineteenth-century children’s author fed up with the Janeway tradition was Heinrich Hoffman. In 1845, Hoffman wrote and illustrated Der Struwwelpeter (‘Peter the Shock-Head’), an over-the-top catalogue of horrific deaths of very mildly misbehaved children that parodies juvenile conduct literature. Der Struwwelpeter quickly became a cult classic, beloved of adult readers. In 1990s London, the cabaret-burlesque band the Tiger Lillies adapted it to create their “junk opera,” Shock-Headed Peter, which became an international success.

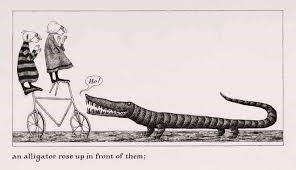

Another parody-children’s-conduct-horror author-illustrator is Edward Gorey, whose black-and-white illustrations of children at the brink of disaster rival Der Struwwelpeter in their neo-Gothic mischievousness. Once you’ve read Gorey’s The Epileptic Bicycle (1969), the tale of the daft young duo Yewbert and Embley’s adventure on “an untenanted bicyle” that uncannily “slides into view,” you won’t ever forget it.

Five years before The Epileptic Bicycle, Dahl published Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which sings in the same minor key, grabbing the conventions of eighteenth and nineteenth-century children’s conduct literature to show Willy Wonka, the elusive, godlike inventor of impossible candies, testing the manners of five randomly selected children and their parents.

The four miscreant children are clearly made that way by their far more antisocial parents, which gives child readers of the book the opportunity to critique adult behavior—a freedom that few other children’s books of the time allow. The book also encourages skeptical thinking about corporate ethics. At its conclusion, Charlie wins the Chocolate Factory itself—because he has behaved well but also stood by and patiently watched, without objection, while Wonka sent the other children and their parents off to seeming certain death, by drowning, various toxic substances, being “sent by television” and even—two decades after the Holocaust—incineration. If you’re able to tolerate this, Dahl suggests, you’ll be able to run a (slave-labor-powered) factory, keeping its products popular and its secrets secret.

The captivating ethical complexity of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory suggests that Dahl was right: horror has a place in children’s literature.

By Dr. Rebecca Nesvet

Rebecca Nesvet is an Associate Professor of English who teaches nineteenth-century British literature, the British novel, modern world drama, and digital humanities. Her research concerns Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and (more recently) “Sweeney Todd” creator James Malcolm Rymer and his radical and Romantic contexts.