I’ve been fascinating with Gilded Age literature ever since I read my first Edith Wharton novel—for fun, in high school. I started with Ethan Frome (1911), one of the darker novels that’s so imbued with the dark, cold, spareness of winter that I think it’s titled Winter. Yikes. Wharton’s novels haunt me with their visions of love denied and seemingly inevitable—and untimely—death lurking behind the glittering façade of the denizens of Old New York. Her ability to skewer the very society that she’s privileged to inhabit has always intrigued me, and even inspired me to write a scholarly analysis of The House of Mirth and Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie.

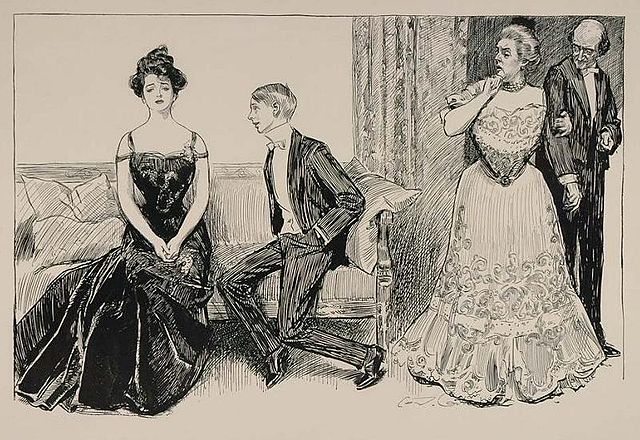

Imagine my delight in discovering Joanna Shupe’s historical romance novels set during the Gilded Age. All the glitter—and struggle—of Wharton and Dreiser with happy endings and love triumphant rather than meaningless, avoidable deaths. Hooray! I recently read the first two books in Shupe’s Uptown Girls trilogy. In The Rogue of Fifth Avenue (2019), Frank Tripp, a favorite recurring character from an earlier series, gets his own story, as he takes on a tricky legal case to help Marion “Mamie” Greene. Mamie, the eldest daughter of a prominent family, is a modern day Robin Hood, who steals from wealthy men at gambling halls, and supports those on the margins of society with this redistribution of wealth. The Prince of Broadway (2020) features the romance between Mamie’s sister Florence, whose dream is to open her own gambling hall for women, and Clayton Madden, owner of the wildly popular Bronze House gambling hall, whose plans for expansion threaten Florence and her family.

Mamie and Florence are shimmering, spirited, talented women who use their considerable economic privilege and status to make the world more equitable. Both women chafe under the restrictions placed upon them by their gender and their status, namely expectations that they marry well. Ultimately, both women reject safe or expected marriages in favor of love with men who are part of the nouveau riche, despite their own status as Knickerbockers—grand, established families. These women are outspoken, plucky, and determined to live life on their terms, flouting the respectability of their father, Duncan Greene, who is a hero in his own right because when push comes to shove, he advocates for his daughters’ happiness.

Frank and Clayton are likewise riveting. Both men are self-made, overcoming family ruin and poverty to become wealthy and powerful. Because of this, their situations are tenuous; the respectability and power they’ve earned can be easily toppled by the established wealthy families they live and work among, including Duncan Greene. I appreciate how Shupe encourages readers to more deeply explore the intersections of class and gender, and how individual fates are always shaped by the social structures that are resistant to change. While Frank and Clayton’s stories suggests the possibility of class mobility, Shupe never lets us forget their precarity. And she shows us the economic privilege the Greene sisters have doesn’t necessarily translate into gender equity. And yet because of romance genre conventions—love and emotional justice triumphant—we see a world where Frank and Mamie, Clayton and Florence all win love, partnership, and security. And their winning enables others less fortunate to win as well, suggesting that individual fates can begin to change those seemingly immutable social structures.

I can’t help but compare Florence and Mamie to Lily Bart, Wharton’s protagonist in The House of Mirth (1905). Lily, like the Greene sisters, cannot face marrying for stability and respectability. Unlike them, Lily can’t convince herself to marry someone on the fringes of society until it’s too late. Trapped in the gilded cage that society has crafted, Lily’s only escape is…tragic. Wharton and Shupe both critique the same social structures, but the romance genre allows its heroines to live their dreams, while literary fiction often sacrifices them in supposedly instructive—and most often dissatisfying or traumatic—ways. This is one reason I most love reading historical romance novels alongside the classics that shaped my identity as a literary scholar. Romance novels suggest that there is always another way to live ones’ dreams and achieve emotional and personal fulfillment that just might begin to transform society as a whole: through love.

By Dr. Jessica Lyn Van Slooten

Jessica Lyn Van Slooten is an Associate Professor of English, Writing, and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Wisconsin Green Bay. She teaches courses on women writers, gender and popular culture, romance writing, and more. Jessica has published numerous articles on teaching and assessing gender studies courses, and popular romance fiction and film. She is currently drafting a romance novel set in a small midwestern town.